Right now, people living in the UK should be terrified, because our government is gambling with our lives and well-being, but doing so with astonishingly bad odds. Everywhere else, people should try hard to ensure their own governments understand how dangerous this gambling is, so that they can avoid repeating it, while mitigating the equally high danger that the UK’s experiment poses to the whole world1.

The gamble I’ll focus on is this: the UK government is acting as if there was no chance that the virus will learn to infect vaccinated people, or people who got infected and survived. This is utter madness, because in fact, it is very likely that the virus will evolve in this direction, and alas, current policies can only speed up the process, multiplying the risk many, many times.

In the words of Dr. Mike Ryan, from WHO: “the logic of ‘more people being infected is better’ is, I think, logic that has been proven its moral emptiness and its epidemiological stupidity”, but alas, this is exactly what the UK government is producing with its explicit policies2.

In response, a number of people, medical doctors, epidemiologists and scientists, led by the Independent SAGE are sounding the alarm (Gurdasani et al, 2021). Their focus is on residual risks of deaths (which isn’t close to zero, even for vaccinated people) and the vastly underestimated impact of long COVID. Their focus is entirely valid! Both aspects, even in isolation, are grave enough to demonstrate the utter stupidity of the official policies. Not attempting to reduce R below 1 and instead hoping that surging infections will not have too bad effects, given the amount and type of people vaccinated, is manifestly reckless, on those grounds only.

However, these valuable efforts are relegating one argument to the sidelines. The risk of breeding a new variant able to escape existing immunity (immunity due to either vaccination or natural infection) is consistently mentioned, but not highlighted. I think this is wrong, for two reasons:

- If such a variant will appear, the damage it will make (in the UK and worldwide) is much, much more than the direct (and deeply concerning) effects of the current policies.

- The current policies are making the appearance of such a variant (or multiple such variants) much more likely. If they can exist, they will appear sooner and in greater numbers.

I don’t think point 1 needs much supporting evidence. If a vaccine-escaping variant will appear, we’ll be once more, defenseless. Only strategy available would be to lock-down again, hard. But this time, we’ll be doing so from a weaker starting point: strained populations, weaker economies, health systems and hospitals already under huge and long-lasting pressure, declining credibility of governments and scientists and so forth. Perhaps new “counteracting” vaccines will become available relatively quickly, but as we know, distribution will still be slow in most of the world and of course, anti-vaxxers will inevitably gain traction, becoming even more dangerous than they already are.

This leads me to the golden rule of risk-management under high uncertainty:

You don’t, ever, gamble with known existential risks.

In high uncertainty situations, when an event is known to be possible, but it is rare enough to have an impossible to estimate probability of occurring, the only sensible policy is to do whatever is possible to minimise its likelihood.

Willfully doing the opposite matches quite well a definition of insanity.

And yet, this government is breaking this golden rule, overtly. Knowing full well that if vaccine resistance will appear, many of us will die as a consequence. It’s as simple and terrifying as that.

Point 2 above is less obviously true, though. In what follows I will claim that it is, in fact, obviously true, but only after putting together enough separate bits of existing knowledge. Thus, I think it is useful to piece these bits together in one coherent argument.

Given the urgency3, I do not have the time to collect multiple references supporting each claim, thus I will merely point to some supporting evidence, picking from the least controversial options I can find quickly.

Obvious fact number one: this virus can mutate, and each new person it infects is a new chance to mutate. Thus, high numbers of infections produce higher chances of mutations.

Obvious fact number two: this virus mutates often (Hudson et al. 2021). We know this from the important sequencing work done in the UK and elsewhere. But even as non-specialists, we can infer this fact, because the various variants of concern (Alpha to Delta and more) did appear and spread. They spread, because they are better than the original virus at spreading (this is a tautology: it can only be true). But this implies that the virus mutated in innumerable other ways, of which only a handful actually made it better at spreading. It happens because each single mutation is random, and finding a mutation that increases infectiveness of an already very infective virus is clearly an extremely low-probability event.

Obvious fact number three: the protection provided by vaccines is fragile. We need many different vaccines for each different pathogen because vaccinations are specific. They teach our immune system to neutralise a specific pathogen, and only that specific one. If the pathogen changes enough, vaccines stop being effective. It’s why we need to get yearly jabs against the flu. The flu virus mutates at a pace that is high enough to make this necessary.

Obvious fact number four: COVID-19 has mutating capabilities (intended as “abilities of finding effective mutations”) that are comparable to the flu. The appearance of several strands, which are better than the original virus at spreading, provides the incontrovertible proof.

Effects of all these obvious facts:

- The random appearance of some degree of vaccine- (and natural immunity-) resistance is more likely than the appearance of each one of the “named” variants (Alpha to Gamma). This is because, to escape vaccines and immunity, the virus needs merely to change. Unlike the named variants, it doesn’t also need to be better at spreading than the currently prevalent form.

- Allowing more infections to happen multiplies the probability of new variants to emerge. It thus makes it incrementally more and more likely that vaccine resistance will appear, with each new infections.

- For a vaccine-resistant variant to appear and spread, one of two things need to apply: the variant needs to be better at spreading on top of its resistance qualities, which is a rare event; and/or it needs to have access to a large-enough proportion of vaccinated people. Until now, the latter case was rare or impossible, because too few people were vaccinated. But as more people do get the jabs, this case becomes not only possible, but also more and more likely (if the virus is allowed to spread).

These three effects are not controversial. They are the inevitable consequence of the obvious facts I’ve listed.

Nevertheless, these days, people expect evidence. Mere reasoning, however inescapable has somehow lost its powers of persuasion, at least when it comes to informing policies (for well known, and understandable reasons!).

Thus, I went through the trouble of demonstrating, with numbers(!), my assertions. This however, is not something that can be done in a scientifically sound manner4, because there are too many unknowns.

We don’t know the exact mutation rate, and even less, the rate of different types of mutations. We don’t know well enough how the virus spreads, and thus, we know even less about the ways in which its spreading abilities can change. We don’t know what mutations will make it better or worse at spreading, nor what mutations will make it better at escaping immunity. However, we do know that each mutation makes it somewhat better at escaping immunity, inevitably, because it makes it a little different.

Still, apparently numbers are more convincing than (inescapable) arguments, so I’ve made a toy model to produce some. In it, we have a set of 4 inputs, which I’ve labelled as “assumptions“:

- Given an infected person, the probability that interacting with one not infected, not immune person will transmit the virus.

- Given an infected person, the probability that interacting with one not infected, already immune person will transmit the virus.

- The proportion of immune / not immune people in the population.

- The number of interactions that an infected person has, while infected.

I don’t need to convince anyone that this is a toy model. It oversimplifies everything! But it is complex enough to account for: changes in infectivity and thus, for the likely effects of mutations (1,2), changes in vaccination rates (3), changes in social-distancing policies and practices (4).

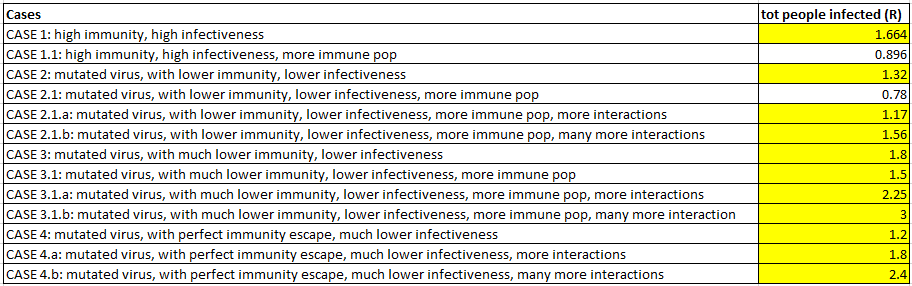

Here is the summary of the findings:

Note: you can download the Excel spreadsheet I’ve used to calculate these figures here. Hopefully, it is organised well enough to allow tinkering with it. It will allow you to check my numbers (please do!) and also to play with the parameters and see how the simulated R value changes accordingly. If you need “more serious” science, please see this preprint (Gog et al. 2021), which supports my (obvious) conclusions, since they demonstrate that “the highest risk for vaccine escape can occur at intermediate levels of vaccination“.

We start with CASE 1: in which I’ve (arbitrarily) picked a combination of variables that result in an R number that is comparable to the present situation in the UK.

I then changed one or more variables to see what effect they have on the all-important (but imaginary: this is a toy model/simulation!) R number. In yellow, I’ve highlighted all cases where the resulting R remains above one. What this toy demonstrates is that it is possible, and in fact, it is extremely easy to find conditions where a mutation that reduces infectivity, but confers some degree of vaccine/immunity resistance, can proliferate. In fact, the families of cases 2 and 3 assume that a mutation conferred some, but far from perfect vaccine resistance, at the cost of reduced infectivity. Cases of family 4 are “limit” cases, where immunity escape is perfect, obtained at an extremely high cost in terms of infectivity. Thus, cases 2 and 3 are clearly much more likely than the emergence of each one of the known variants of concern (Alpha to Delta), while case 4 might be of comparable likelihood (but we really can’t know!).

This is why we should all be terrified: my model (limited as it is) already demonstrates that, when a significant amount of the populations is indeed vaccinated and/or “naturally immune”, vaccine resistant variants, able to spread at exponential rates, are MORE LIKELY than the appearance of each of the known variants of concern. [For those at the back: the variants of concern were likely, enough for them to actually happen; it follows that anything that has now become more likely than those will, oh, probably happen!]

From here, one has to conclude that, precisely because we now have a partially vaccinated population, allowing the virus to spread is utter madness. It multiplies the probability of a catastrophic event, which has, by definition, the potential of killing millions of us.

Moreover, the same toy model is already powerful enough to also show what governments should do.

Looking at “CASE 1.1: high immunity, high infectiveness, more immune population“, is all we need. To minimise the existential risk of producing a vaccine-resistant variant, whenever a significant proportion of the population is vaccinated, governments should do all they can to keep infection rates as low as possible. They should also keep vaccinating the population, until they reach a situation equivalent of CASE 1.1, where R is naturally below 1 and therefore COVID-19 is dying out, allowing to finally reduce social distancing measures, SAFELY!

Following this route, with a bit of luck (i.e. if vaccine resistance won’t emerge despite our sensible efforts to prevent it) would lead to the extinction of COVID-19. I believe we all agree that’s desirable.

However, the UK government is doing precisely the opposite of what is beyond doubt the optimal strategy. We can and perhaps we should admit that the optimal strategy might be impractical: we need some freedoms, after all… However, the current situation would not require us to all go back to a hard, “do not leave home”, prolonged lockdown: any social-distancing measure will reduce R of some amount. Thus, any social-distancing measure is, right now, better than nothing. But that’s a million miles from “let’s remove all restrictions”, which is, if we won’t stop them, what the UK government is going to do.

Overall: the UK government is doing exactly all it can to produce vaccine-resistant variants.

Which counts as something worse than being “morally empty and epidemiologically stupid”, I’ll leave it to your imagination to figure how I call this government in the privacy of my own mind. The same names apply to Prof Chris Whitty and Sir Patrick Vallance, whose duty is to explain the above to our ministers and the population. They are both clearly failing to do both things and thus, given that they are not resigning (nor threatening to) they are overtly complicit with all this madness.

Now please go and sign this document, where the specialists from Independent SAGE (and more) express their overall (entirely correct) disagreement with the current plan.

Notes and Bibliography

1. This post is very UK-centric, in a way I find uncomfortable. It is important to note a few things, from a more global perspective: first, what is happening in the UK poses a danger to everyone on earth, because the virus does not respect borders, given that border controls are not watertight in most cases. Second, many more countries are making or are about to make similar/equivalent mistakes, which are, or will be, equally dangerous. Third, the argument I’m making here can and should be used to reassert the need of a fairer distribution of vaccines world-wide. For reasons of length, I have, with regret, decided not unpack any one of these points here.

2. For those who don’t know, starting on July 19th, the UK government is planning to remove all restrictions to businesses, remove all social distancing rules, including legal obligations of wearing masks, reduce border controls and withdraw the availability of free lateral-flow tests, while not issuing obligations or even guidelines promoting the provision of adequate ventilation in indoor spaces.

3. Urgency: yes, this is really urgent. We need to find a way of making the UK government to make a spectacular, and presumably unpopular, U-Turn. Unfortunately, it is a race against time. Every day that passes in the current situation multiplies the probability of the appearance of vaccine resistance. Thus, every minute counts.

4. Scientific manner: there simply is too much we don’t know. For example, producing a “non-toy” model of how selective pressure may change as vaccine resistance mutations appear, in order to be “accurate” (and therefore: not a toy) requires to have accurate estimations of mutation rates, as well as of an idea of how many will produce vaccine resistance and to what extent. Presently, we are still debating how much vaccine resistance the Delta variant has, which is a variant that does exist! Thus, such attempts, interesting as they are, cannot and should not be taken too seriously.

Gurdasani D, et al. Mass infection is not an option: we must do more to protect our young. The Lancet. July 07, 2021 DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01589-0

Hudson B S, Kolte V, Khan A, Sharma G. Dynamic tracking of variant frequencies depicts the evolution of mutation sites amongst SARS-CoV-2 genomes from India. J Med Virol. 2021 Apr; 93(4):2534-2537. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.26756.

Gog JR, Hill EM, Danon L, Thompson R. Vaccine escape in a heterogeneous population: insights for SARS-CoV-2 from a simple model. medRxiv. 2021 Jan 1. DOI: 10.1101/2021.03.14.21253544